Preserved in Oil, by Ruth La Ferla

Society portraits, many in a formal style worthy of Sargent, are in vogue again.

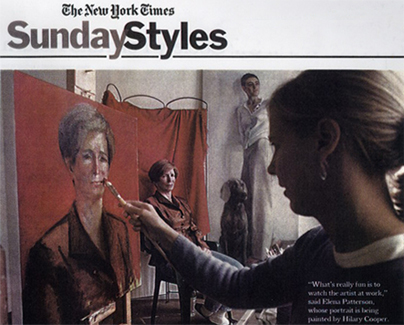

Her spine buttressed by a pillow, her coppery hair set off by the russet shawl draped behind her, Elena Patterson sat for Hilary Cooper, a New York portrait painter, a picture of comely repose.

In a lambent corner of the studio where Ms. Cooper works in Long Island City, Queens, the two savored a moment of easy intimacy. “What’s really fun is to watch the artist at work,” Ms. Patterson said, glancing at Ms. Cooper, who stood in a beat-up crew-neck sweater and jeans, applying steaks of rusty brown to her canvas.

So restful was the scene, so evocative of the languor once famously captured in oils by John Singer Sargent, that you half expected a retainer to appear bearing a bright silver tea service.

Ms. Patterson, 57, found the ambiance enchanting. “This is another world,” she said, brushing aside a stray swatch of hair. “I’d say that it’s old-fashioned, and that definitely appeals to me.”

The scene did indeed conjure up an earlier epoch, a more gracious and leisurely age, when people embarked on grand tours, collecting bibelots along the way and having their likeness rendered by the leading painters of the day. As well it might. The fin de siècle tradition of society portraiture is back at the fin of this century, with clients ranging from Diane Von Furstenberg to George Plimpton to Hilary Auchincloss. Portrait shows of Sargent and Ingres, whose names once elicited yawns, are suddenly proving to be hot at the box office.

“A big fact is that portraiture is on the rise,” said Robert Rosenblum, the art historian who wrote the introductory essay for the Ingres show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Bravura painting of a Sargent or a Giovanni Boldini “used to be thought of as irrelevant trash,” he continued, adding, “Now these artists are hot stuff again.”